Comirnaty or Comirnaughty?

Fishy Findings from the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID Vaccine Clinical Trial Data - A Summary

Last week I was on the Rounding the Earth podcast along with my recent collaborator, Pierre, of OpenVAET to talk about “the nitty gritty details of Pfizer’s falsehoods.” We presented a summary of key findings from several months of digging into the Pfizer clinical trial data. Most but not all of those findings have been published in very detailed and thorough posts over at Pierre’s blog and should have been mailed out to my subscribers as well.

This post is meant to provide an overview of what I view as our key findings. This is a long post, as it summarizes months of painstaking work. If you prefer to watch or listen to our presentation, here is a link to the podcast, which runs about 90 minutes:

https://rumble.com/v2k9k6g-the-nitty-gritty-of-pfizers-falsehoods-round-table-w-josh-guetzkow.html

SUMMARY

First, a quick summary of our key findings:

There are 301 subject IDs missing from the data without explanation. As detailed below, the pattern of missing subjects leads us to believe that these cannot all be explained by error and that some may have been deleted to hide something.

Cases of suspected but not confirmed COVID-19 were not to be counted in adverse events. We know that in at least two cases at two sites, the study sponsor (BioNTech) called the site to ask them to reclassify an adverse event as Suspected COVID-19. We also know there was an unblinded study-level medical monitor checking adverse events for signs of vaccine-enhanced disease. This creates a mechanism for adverse events to be swept under a rug as the study was still going.

There is evidence of widespread lack of blinding due to imbalances in protocol deviations.

The large imbalance in the number of treatment and placebo subjects who were excluded from the efficacy analysis due to important protocol deviations is almost entirely due to problems with the storage or preparation of the vaccine leading to treatment subjects being excluded. However, there were an equal number of positive PCR tests among treatment and placebo subjects excluded for this reason, so including would not have had a significant impact, if any, on the efficacy analysis.

There are significant imbalances between treatment and placebo subjects in rates of central and local PCR testing after reporting COVID symptoms. Treatment subjects were significantly less likely to get tested locally, and prior to the data cutoff date for the analyses that the EUA was based on, treatment subjects were less likely to have a central PCR test compared to placebo subjects.

Treatment subjects who had a positive local PCR test were significantly more likely to have a negative or missing central PCR test than placebo subjects.

BACKGROUND

The discussion began with a bit of background that my readers are probably familiar with: documents and data submitted to the FDA for the approval of the Pfizer/BioNTech clinical trials for their COVID-19 vaccine have been released via a court order as a result of a lawsuit brought by Public Health and Medical Professionals for Transparency, and more are continuing to be released every month. The site that houses the released data is here. A handy tool for searching those documents can be found here.

We then went on to talk about how long the trial actually lasted, which you can read more about at my post here:

How Long Did the Pfizer COVID Vaccine Trial Last?

How long did the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID vaccine clinical trial last? The short answer is: 97 days. Here’s the long answer: When unblinding began in earnest on December 14, 2020 — with the FDA’s blessing 3 days after they granted an EUA — the trial subjects in the Phase 2/3 trial for ages 16+ had been in the trial on average for 97 days. That's 3 months pl…

Missing Subject ID’s

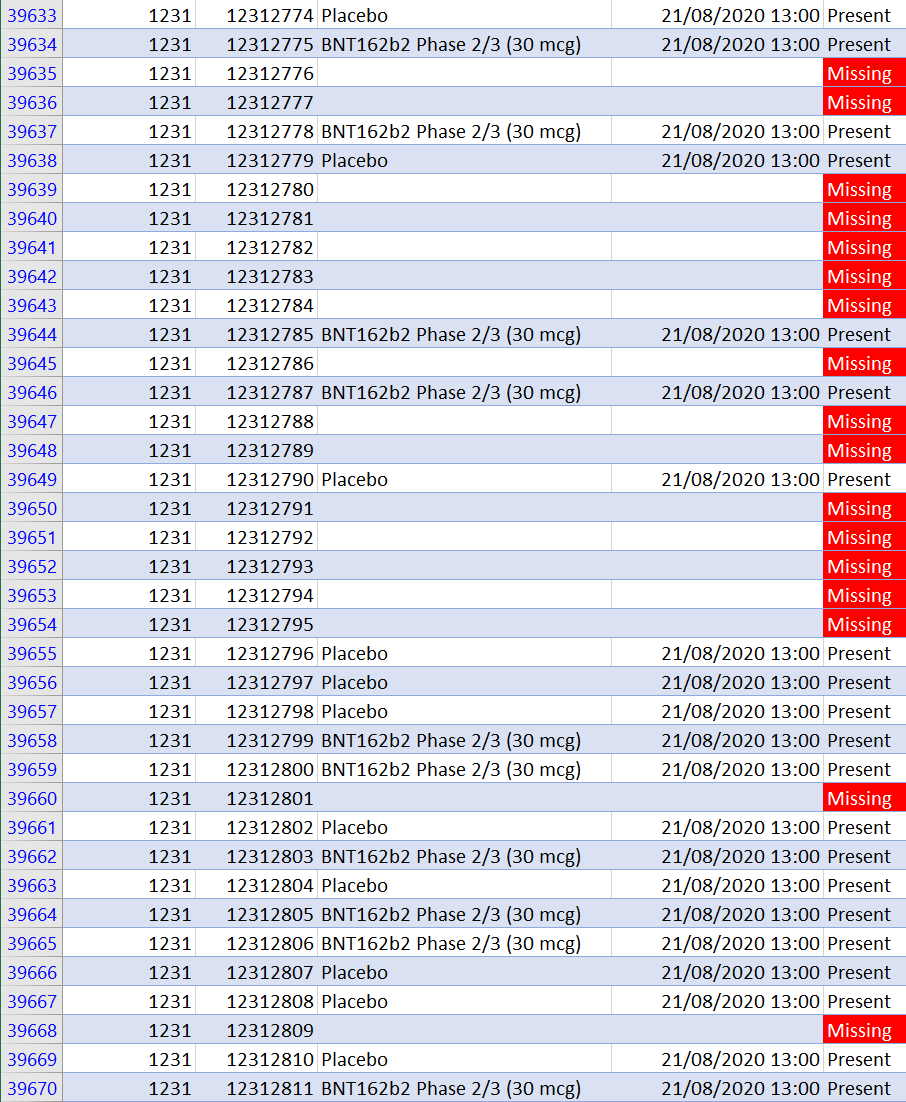

We then discussed what I view as potentially our most important finding: there are 301 missing subject ID’s in the final Pfizer dataset. What does that mean? When potential subjects who had already been pre-screened over the phone showed up at one of the research sites, they would be assigned a subject ID number prior to a second round of in-person screening at the trial site. Subjects who failed the screening as well as those who were eventually randomized in treatment or placebo were assigned subject IDs by the software used to manage the trial. The system assigned subjects consecutively, starting at 1001 at each site: 1001, 1002, 1003, 1004, etc. We found 301 places where the subject ID numbers were ‘missing.’ So you’d get a sequence like 1001, 1002, 1004, etc.

What’s the big deal? Couldn’t it just be computer or human error? Yes, it could be. But there are several indications that at least some of these missing IDs are not simply due to error. The concern is that at least some of these subjects were erased or removed from the dataset to hide an inconvenient outcome, like a serious adverse event such as death. The data released is basically a snapshot of the database from March 13, 2021, so the missing subjects could have been removed at any time prior to that. We know that the research sites at least had the power to request the removal of subject IDs.

We have reasons to think the missing 301 IDs are not (entirely) honest mistakes. To begin with, if it was just random error, we would expect the missing subject ID’s to be randomly distributed across the sites, but they’re not. They are concentrated in handful of sites. We would also expect to see single ID numbers missing. But in many cases we see 2, 3, 4, 5, even 8 or 9 consecutive ID numbers missing. Here is a breakdown of the number of gaps we have of various sizes:

Most concerning is that an outsized proportion of missing ID’s come from the Argentina site, which has 12% of all trial subjects but 37% of all missing subjects. The largest number of missing subjects (17) in a single day (which includes the gap of 9 consecutive missing ID numbers), comes from the Argentina site. Here is what some of that looks like:

Particularly suspicious, though, is that these 17 missing subject ID’s are all from the same day that Augusto Roux was enrolled and given his first dose, Aug 21, 2020. That also means that they would have been scheduled to receive their second doses on the same day he did. If his serious adverse event (including pericarditis) after the second dose was due to a bad or poorly prepared batch administered that day, perhaps there were other subjects that day who were entirely erased from the data to hide their negative outcomes. We can’t say for sure, but in principle it’s possible. For more on Augusto, see my post here:

Is Subject #12312982 the Key to Proving Pfizer Vaccine Trial Fraud?

Subject # 12312982 in Pfizer study C4591001 is Augusto Roux, a 35-year old lawyer from Buenos Aires, Argentina who volunteered for Pfizer’s stage 3 trial of its COVID-19 vaccine (or whatever you want to call it) in order to protect his mother with emphysema.

There was another finding related to a gross incompatibility between the subject level data on the number of screened and randomized subjects at each site and a pdf summary document that was submitted as part of the Biological License Application (BLA). We wrote to the FDA to ask them about this problem and the missing subject IDs. They said they’d get back to us. We’re still waiting…

For more on all that problem and more details on the missing IDs, see this post:

SWEEPING ADVERSE EVENTS UNDER THE COVID RUG

There is another reason why the Augusto Roux story matters. The trial site incorrectly recorded his adverse event as pneumonia, but a little while later the project sponsor (BioNTech) contacted the site and asked them to change his AE to ‘Suspected COVID-19’ even though his PCR test at the hospital was negative.

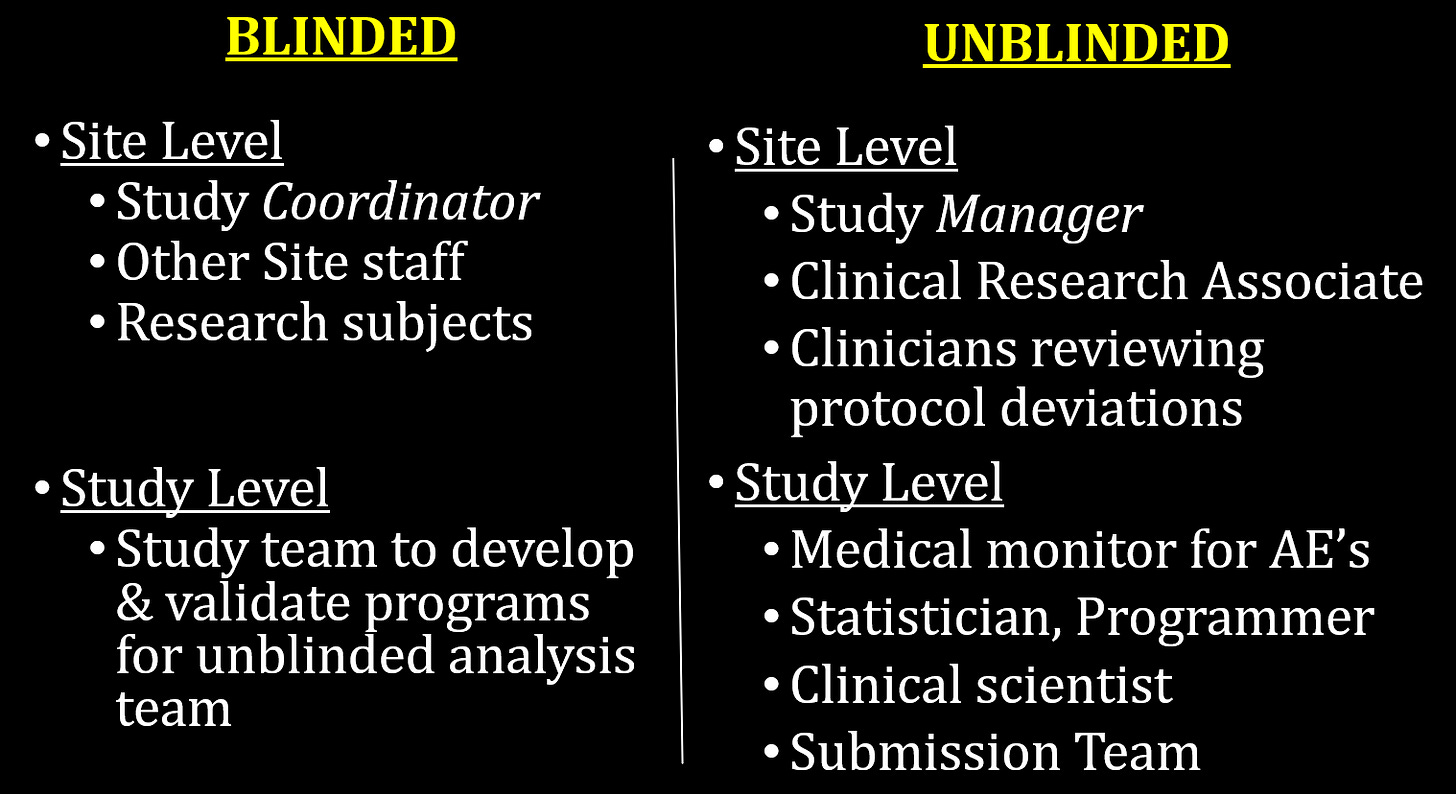

How is it possible that the trial sponsor could call sites asking them to change subject adverse events to ‘suspected COVID-19’ while the trial was ongoing? The answer is because the trial wasn’t double blind. I cover that in the post below, where I go into detail on the the “Swiss Cheese” method of blinding used in the trial:

The Pfizer Vaccine Trial Was Not Double Blind

As people being digging into the detailed records of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine trial released by the FDA, there is something they need to understand about how the trial was run. Recently, people like Ed Dowd have pointed out that, in light of the scandalous malfeasance at one of the Pfizer vaccine trial sites

Here is a breakdown of the blinded and unblinded personnel at the site and study levels:

The key here is the unblinded medical monitor for AE’s at the study level. The justification for unblinding that person was because they were concerned about vaccine-enhanced immune response or antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), so they wanted somebody monitoring the AEs for signs of enhanced COVID-19. What they didn’t say was that that person was going to have the authority to ask sites to change their coding of adverse events.

Here’s why this matters: according to the protocol, cases of suspected COVID-19 were not to be counted as adverse events. And since they were unconfirmed they wouldn’t be counted as COVID cases in the efficacy analysis either. So by redefining an adverse event as suspected COVID, they could make it disappear. The trial was designed with this giant rug under which adverse events could be swept if needed. And they did. As evidence of this, here are the adverse events recorded for Augusto according to the clinical trial adverse event data:

This is no way resembles what happened to him in the hours and days following his second jab. You can read more about that in my post on him above, which also has links to David Healy’s more extensive coverage of Augusto’s ordeal. Also, the AE of anxiety had no basis in fact, and was assigned by the PI without any formal diagnosis.

We don’t know how frequently this happened, but we know it happened in this case, and we know of one other where the trial site refused to go along with the request. In the large subject-level adverse event file, this is the only case of Suspected COVID-19 Illness listed. But we know from trial report documents there were thousands of cases of suspected COVID-19 among both treatment and placebo subjects. Most of these were just subjects reporting mild symptoms like cough or headache. But it seems not all of them, as we’ve been unable to replicate the numbers reported in the official trial reports based on reporting of COVID symptoms alone, leading us to wonder if there were additional cases where adverse events were recoded as suspected COVID-19 that are not in the AE file. More on this here:

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE OF POOR BLINDING

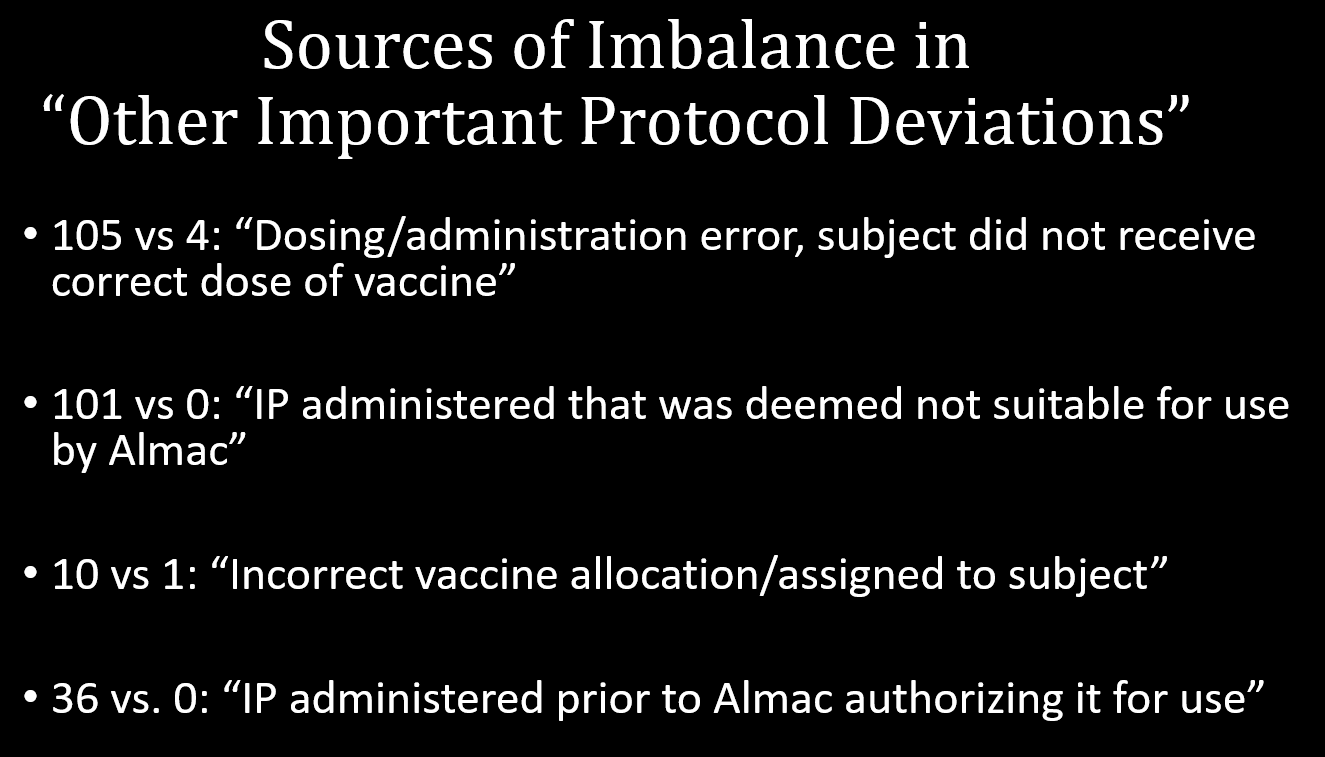

Other evidence of poor blinding comes from a series of imbalances in various protocol deviations in the placebo and treatment arms. Whenever there was a deviation in the protocol, it was supposed to be recorded. For some deviations, there could be a valid reason for an imbalance across the treatment and placebo arms, but for others there is no obvious reason why you would have more protocol deviations in one arm versus the other except as a result of different behavior on the part of the investigators or the subjects due to poor blinding. Here are a list of such imbalances in protocol deviations, all of them statistically significant and all of them occurring before subjects were officially unblinded:

SUBJECTS EXCLUDED DUE TO IMPORTANT PROTOCOL DEVIATIONS

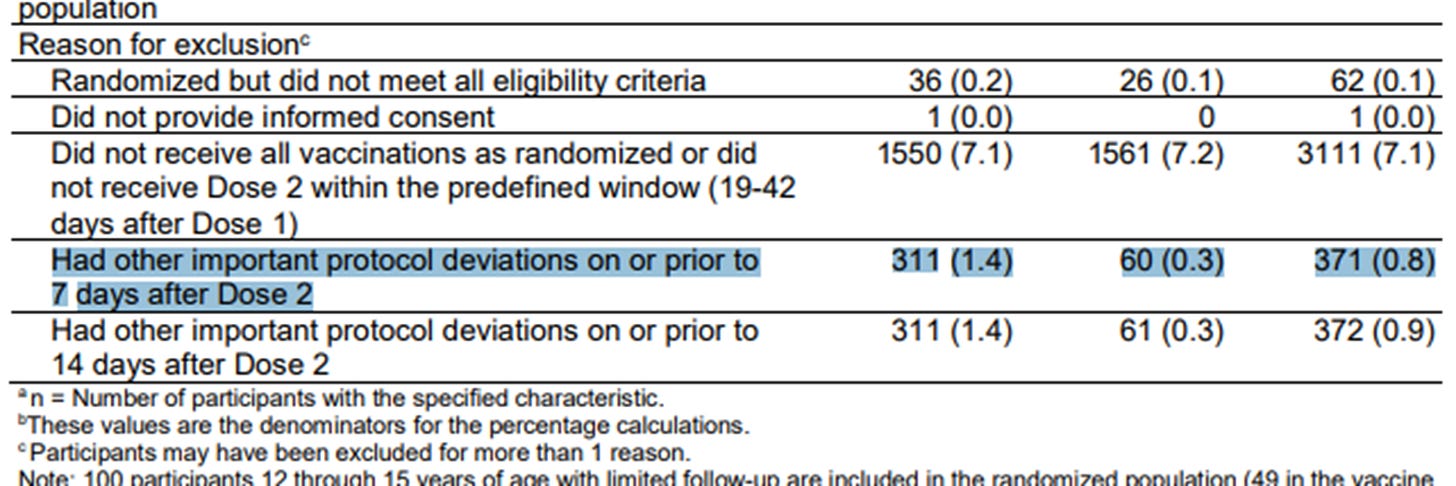

The highlighted row below from a table from the efficacy analysis used for the EUA has received a lot of attention. It shows there were many more people in the treatment group excluded from the efficacy analysis compared to the placebo group (311 vs. 60) due to ‘other important protocol deviations.’ This raised the concern that COVID cases in the treatment group were being removed from the analysis in order to skew the results, which were based on less than 200 COVID cases overall.

But now we have the subject-level data so we can check what important protocol deviations they had and whether they were recorded as PCR-positive. It turns out that the reason for the imbalance is almost entirely due to problems with the vaccine. Here is a rundown of the protocol deviations related to the vaccine among the excluded subjects with a comparison of numbers in the treatment vs placebo group:

Moreover, although all of these excluded subjects reported at least one official COVID symptom prior to the data cutoff date of Nov. 14, 2020, only 10 of those came back positive — 5 in each group. Although observers were right to be concerned about this imbalance, it doesn’t seem that it would have changed the results much if at all. It underscores, however, just how difficult it is to ensure the quality and integrity of vaccine transport, storage and on-site preparation — even under ideal conditions. Imagine how much worse it was under real life conditions with a rollout of unprecedented scope and speed. More information on these exclusions is in this post:

PCR TESTING IMBALANCES - LOCAL VS CENTRAL

Here we get to some very important findings. To understand them, we have to understand how COVID cases were identified in the study. According to the protocol, subjects with symptoms were supposed to call their research site to report them. They would then be asked to come in for a PCR test to be sent to the central lab or to swab themselves with an at-home kit they had been given and to send it in to the central lab. Where was that central lab? It was at Pfizer’s Pearl River laboratory in New York. As Jikky pointed out in the tweet below, that’s an awful long way to send a test, especially from South Africa(!) or Buenos Aires:

Jikky is drawing our attention to the absurdity of having all the testing for all of the sites — no matter how far-flung — go all that way to be done in a central lab. The same assay could have been used at any of the research sites. All of the tests to determine COVID cases (and thereby the efficacy of the vaccine) were done at a central laboratory controlled by Pfizer. If they knew which swabs belonged to treatment and placebo subjects, it would be trivially easy for them to manipulate the outcome of the trial — for example by using different cycle counts. Matthew Crawford has hypothesized that the PCR test has never been validated for having equal accuracy among vaccinated and unvaccinated. There are other potential explanations.

Now, in addition to the central tests, local tests were also done, since the central test results would take weeks to come back. Local tests were sometimes done at the research site, but often they were done through subject’s primary care physicians or at a local lab, pharmacy or hospital. These results were also supposed to be recorded in the trial records. Importantly, Pfizer did not have direct control over the results of these tests.

One last bit of important background information is that the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) was granted by the FDA on Dec. 11, 2020 based on clinical trial data up through Nov. 14, 2020 (the EUA cutoff date).

Local Testing Rate Imbalance

When we look at the rate at which symptomatic subjects had local tests, we see two things:

Treatment subjects have statistically significant lower rates of local testing. Yes the difference is small but remember that the EUA efficacy calculations were based on less than 200 cases, so even a small difference could make a large impact on the efficacy calculation.

Local testing rates after the EUA cutoff were significantly higher than before the cutoff, for both treatment and placebo subjects.

We don’t know why this is the case. In theory, local tests may have been more widely available as time went on, which could explain the increase over time but not the imbalance across arms. The imbalance across arms could be due to subjects in the treatment arm being more likely to know or believe they were inoculated (due to poor blinding) and so they were less inclined to go to the trouble of getting a test for a disease against which they had been inoculated.

The concern, however, is that something else was going on that discouraged local testing or even involved hiding local testing results that conflicted with the central test. A positive local test was not enough to invalidate the results of a central test, but a record of a positive local test and negative central test could perhaps be considered evidence that the central tests were being manipulated (more on that below). Of course this is speculation — we don’t know the explanation for this imbalance, we only know it exists even though it shouldn’t.

Central Testing Rate Imbalance

In theory, every subject who reported symptoms should have been swabbed and have central test results. In practice, only about 86% of subjects did. When we look at overall rates, we don’t see an imbalance in the rate of central testing. But when we compare the pre- vs. post-EUA period, we see:

Symptomatic treatment subjects were less likely to get a central test than placebo subjects in the pre-EUA period.

Overall central testing rates for both arms increased after the EUA.

All these differences are statistically significant. We cannot tell from the trial data whether a central test is missing because a swab was never taken or because the results were never recorded. Yes, the differences are small, but again the numbers needed to establish efficacy for the EUA were very small and therefore subject to subtle differences. The testing protocol for symptomatic subjects and availability of central tests was the same throughout the trial and for both arms.

More on these imbalances can be found in this post, which also discusses how they are concentrated at a handful of sites:

Imbalance of Test Results across Arms

Finally we get to a finding of critical importance, which has not been published elsewhere yet.

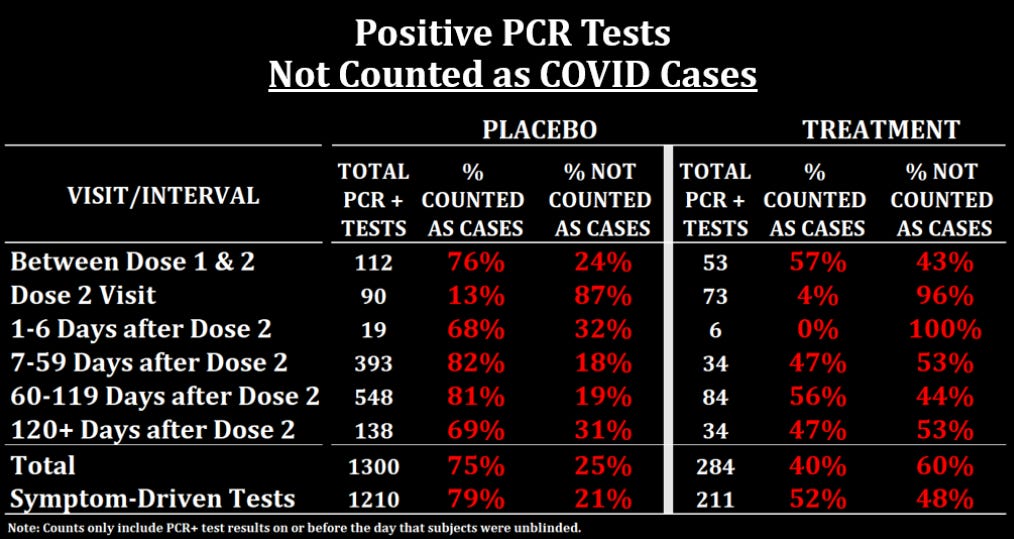

The trial protocol stated that in order to be counted as a COVID case for the efficacy calculation, subjects had to have at least 1 of 9 COVID symptoms and a positive (central) or approved local PCR test within 4 days -/+ of symptom onset/resolution. They submitted a PDF document with a list of all the symptomatic COVID cases that could potentially be used in the efficacy analyses on the basis of that definition. If we compare that list to the subject-level data we have on test results, we see that treatment subjects with a positive test result were much less likely to be considered a COVID case for the efficacy analysis.

The key line to look at is at the bottom, where you can see that only 52% of treatment subjects with a positive symptom-driven test were counted as COVID cases while 79% of placebo subjects were. What explains this imbalance? The answer is that the table above counts any positive local or central test result as a positive PCR. But if we look at local and central tests separately, we find the answer:

Symptomatic subjects in the treatment arm who had a positive local test result were more likely to have a negative or missing central test result.

Here is a table summarizing the numbers:

So if we look at all symptomatic subjects with positive local test results, 31% of treatment subjects had a negative test result compared to 11% of placebo subjects, and 12% of treatment subjects had a missing central test result compared to 6% of placebo subjects.

Keep in mind that a negative central test trumped a positive local test in determining infection, and in order for a positive local test to count in the absence of a central test, it had to be done using one 1 of 3 particular PCR assays.

Also be aware that this result has not been fully confirmed by Pierre yet. He did a similar analysis with the same conclusion but slightly different numbers. We still need to iron out our differences and the exact numbers here are subject to change. On a personal note, I will add that I have nothing but glowing things to say about Pierre as a person and a gifted data analyst, and I our hope our partnership continues to bear fruit.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST

By defining COVID cases as having one of nine symptoms plus a positive PCR test, they were able to ignore asymptomatic cases and pronounce such absurdities as this (which unfortunately was not an April fool’s joke):

But a look at the data shows that there were 6 people in the treatment group at the South Africa sites who had a PCR+ test when they got their second jab, and 5 additional who had a positive Nucleocapsid antibody serology test one month after dose 2. So this statement is only true under a very narrow definition of COVID-19 case. In the real world of course, anyone with a positive PCR test was considered to have COVID, along with all the consequences in terms of quarantine, exclusion and fear.

Comirnasty.

We have spent more time analyzing Pfizer's B.S. than either the FDA or the CDC, and probably both combined. There is a message in that. (Determining that message is an exercise left for the curious reader!) Also, when in doubt, please recall The Bad Cat's First Pfizer Postulate. Pfizer doesn't make mistakes; they make choices.